Great Condurrow Mine

Artist Lucy Gunning reflects on this field trip, which included an exploration of the upper levels of Great Condurrow, an eighteenth-century tin/copper mine, and visits to King Edward Mine and to the Analytical Lab at Camborne School of Mines.

Field trip led by Sam Hughes of Camborne School of Mines, University of Exeter.

Six weeks have passed since the Penzance Convention; I write this now in London.

Most journeys start before they have begun; this one was no exception. There was the anticipation of going down ‘The Mine’ and thinking generally about ‘Extraction’. Coincidently one of my students introduced me to the computer game Minecraft. Evidently there is a whole scene where gamers stream live footage and audio of their gaming onto the net. I watched his ‘found footage’ of a gamer hacking his way through rock / pixels revealing new passage ways, trying to avoid the lurking pitfalls and creatures, while casually chatting about his house, DIY, his relationships, with incredible intimacy and familiarity to not only his imagined anonymous audience of other gamers, but potentially the rest of the world. I found myself feeling claustrophobic, unsure if it was the image of the mine or the life he was describing.

The mining of tin brought the invention of the tin can and the storage of food, which in turn led to war no longer being seasonal. The pragmatics of war rarely get spoken about, but war and the mining of metal seem to have always been intertwined. I pondered also on the word mine and why it should share its spelling with the possessive pronoun ‘mine’. In art terms I thought about Robert Smithson’s desire to screen a film deep inside a cave, which led me to think about Plato’s cave and the illusions encountered there. I also stumbled across a reference to a work by the artist Joelle Tuerlinckx, which makes visible the distance miners travelled underground. So with all this in mind I set off to Cornwall and Field Trip 2.

What appeared to be an unsuspecting small corrugated iron shed was in fact the entrance to Great Condurrow Mine.

It felt counter-intuitive to trust the rusty handrail around the top of the hole, to say nothing of the vertical descent. Normally my visits to Cornwall involve being outside as much as possible – it was strange to willfully go into the darkness. Only one person could descend at a time. We were given practical advice – ‘look straight ahead and always have three points of contact with the ladder’. But I had already looked down. I had to steel myself before taking that initial step on the ladder, the first ladder being about 25 ft to a metal grill platform, to another ladder the same length, then two shorter 10 foot ladders, the first to a wooden platform and the last to what appeared to be solid ground, but we had already been informed that this in fact was compressed loose rock.

The ventilation system had been on for a couple of hours to clear any radon that would have accumulated there. We walked on, Tony and Sam interjected points of interest. Someone asked if there is anything living down there – surely the rock is living I thought. Sam pointed to the answer, bacteria growing on the wood. Radon, bacteria, no solid ground, this seemed like a dangerous place. I found myself diverted by the settings on my camera. It was darker than it appeared, we were all wearing hard hats with lamps attached that gave the illusion of light, but my camera was less easily fooled. We looked at the old equipment still down there for drilling and taking samples. The process of excavating the tunnels with explosives was explained. One imagined an incredibly slow process; a lot of time had been spent down here. The process of analyzing the rock mass for signs of ore was explained. We saw a seam and the vivid leaching copper-sulfate was unmistakable. After an hour and a half we emerged and things seemed a bit different, the ground no longer solid and the grass a bit more springy – plus the doing of it had felt like a milestone.

Our next stop was King Edward Mine. The architecture caught my eye, a sort of utilitarian hamlet. One building was a working museum, a processing plant demonstrating methods used when mining in Cornwall was at its peak. We were shown the processes of crushing, water separation and gravity used to extract the metal out of the ore. The machines themselves showed evolutionary thinking, the gradual refinement of a primitive process. They were switched on.

One was like a vast slanted tabletop with ridges; it shook back and forth. The finely ground rock was dispersed with water, the movement caused the tin, as it is lighter, to rise up to the surface of the table and more water pushed it over the edge and into its own trough. Another part of this building was like a formal museum with vitrines. In one there was a mound of crushed rock, next to it was the approximate amount of tin that it would have produced, a tiny ingot. I asked what tin would have been used for at that time (1850s); the reply was ‘pewter’. Now, retrospectively, this seems like a lot of effort for a plate that wouldn’t break, but at the time it must have been phenomenal, and they must have had a hunch it was leading to greater things.

Someone commented on an early photograph showing an outdoor processing plant with women wearing Victorian dress standing next to vast water channels in the ground. Evidently women did work above ground in some plants, but a woman down a mine was considered bad luck.

Lunch in the local pub, with half a pint of Tinners and much discussion: radon, claustrophobia – Sam describing moving through a very confined space underground and having to remove his battery pack in order to get through – celebrity science and the Brian Cox phenomenon etc.

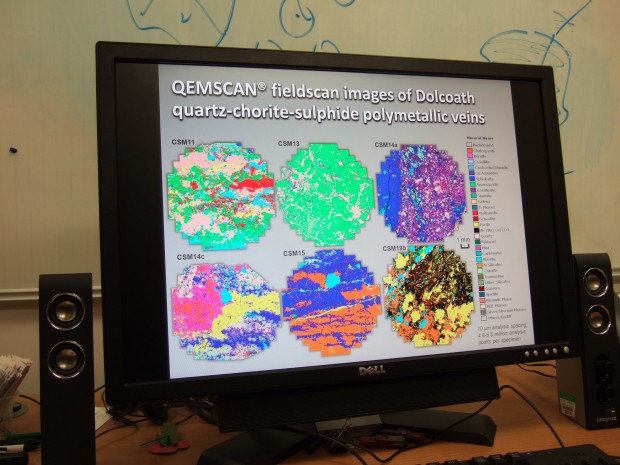

At Camborne School of Mines we were greeted by Professor Frances Wall – and a vast rock collection. Here we were introduced to Dr Gavyn Rollinson, an eminent geologist who manages Qemscan, their scanning electron microscope, the only one of its kind in a university in Europe and one of only a few in the world. In Gavyn’s office a computer screen displayed a Sun Newspaper article with the headline, ‘There’s indium in them thar hills’. Indium is an essential ingredient of any touch screen technology – ipads, phones etc. – and future technology depends on it. Its recent discovery in Cornwall could bring huge economic changes to the region. Gavyn analyses rock; he showed us a sample, powdered rock set in resin. When it scans, Qemscan gives visual quantitative information.

The result was like a colour-coded map of the different elements. He showed us another computer that gives information as a graph and another that gives data. He told us how companies use this facility at CSM and archaeologists have too. Ancient pottery scanned can help reveal where the clay came from and early trade routes etc. Blue-tacked to the wall next to lots of charts and data were a collection of small bits and pieces, a tiny spring, metal parts, plus two bits of plastic, one like a computer plug, both with burn marks on them. This was Qemscan’s predecessor, which Gavin discovered smouldering away, testimony to laboratory geology having risks of its own.

By this point facts were becoming fiction in my mind. Extraction, I was full to the brim. The tin shed had been the portal to a dark and thrilling place. At CSM we’d been back and forth in time, ancient pottery to state of the art technology, and Cornish rock potentially facilitating the virtual world.

Read more about the partnership with Camborne School of Mines for The Penzance Convention.

Read more about this field trip in the Programme listing and view Robin Shail’s presentation (002).